By Ed Ball, CEng, MIPEM, MIMMM – Manager, Intelligence & Strategic Execution

Delays! Rejections! Frustrations!

Inconsistent descriptions of the intended use throughout the submitted technical documentation is commonly cited as the reason for Notified Body questions during EU MDR assessments. Incorrect assignment of the product code or inappropriate selection of a predicate device, based on a poorly defined intended use, can lead to significant delays or failures in US 510(k) submissions.

Introduction

Hopefully most readers of this blog appreciate the importance of the intended use in the design, development, conformity assessment and marketing of a medical device. The intended use should be the starting point for product development and risk management activities. In most established medical device regulatory frameworks, the intended use is fundamental to the conformity assessment of the device.

The intended use drives:

- the classification of the device, and thus the conformity assessment pathway;

- the level of objective evidence required to demonstrate that the device is safe and effective;

- the specific document types required by a regulation;

- the standards applicable for the device;

- the suitability for national reimbursement categories;

- and the resulting surveillance activities once the device is on the market.

The intended use is therefore a significant factor that affects the overall timeline for developing and launching a medical on a specific market. The elements of the intended use are thus critical to premarket regulatory strategies, reimbursement strategies and commercial strategies for sales and marketing.

But what is the intended use?

It is unlikely to be single sentence or statement, I am fairly sure of that. The various facets of the intended use are not something that can be condensed into a short pithy one-liner, without a significant loss of detail and specificity. Although, specific regulatory authorities may require such a statement or headline to act as a summary for all the detail that lies beneath. For example, relying solely on a intended use statement to underpin the technical and clinical evidence to support a submission under the EU MDR or IVDR is likely to be a flawed approach. The use of a high-level statement will likely leave gaps and misalignment when it comes to identifying similar products, identifying and interpreting your user needs, collecting and analysing clinical data, and establishing relevant clinical performance outcomes. None of which are positive when it comes to a successful conformity assessment.

It is unlikely to be single sentence or statement.

How is it defined?

A time-consuming trawl through the ISO Online Browsing Platform, various ISO and IEC standards, several key regulations and numerous IMDRF and GHTF guidance documents gave me the information I was seeking. Regulations do not specify the source (either direct copy or of the ‘inspired by’ indirect variety) for the legally defined terms and definitions, but ISO and IEC standards usually do. Through various convoluted family trees and revision trees, I can tell you that for those medical device standards that define intended use (or intended use / intended purpose as synonym) and cite a source for their reference they lead back to one of the following three documents:

- ISO IEC Guide 63:2019 (Guide to the development and inclusion of aspects of safety in International Standards for medical devices),

- IMDRF/GRRP WG/N47:2024 (Essential Principles of Safety and Performance of Medical Devices and IVD Medical Devices), or

- IMDRF/GRRP WG/N52 FINAL:2024 (Principles of Labeling for Medical Devices and IVD Medical Devices).

It is worth noting that several of the references to ISO IEC Guide 63:2019 are indirect, often via ISO 14971:2019 which uses Guide 63 as its source reference for the definition of ‘intended use’. It should also be noted that the definition in the above two IMDRF guidance documents is the same, where N47 has two Notes to the entry and N52 only includes the second of those two notes. It is also noteworthy that ISO 13485:2016, despite being a major part of the global medical device landscape, neither defines intended use (or intended purpose) nor explicitly requires it to be determined or documented. I can wait whilst you go and check for yourself if you’d like.

Comparing the definitions from these three sources plus those from the EU MDR, EU IVDR and US 21 CFR 801.4 (Table 1), there is good consistency. One could argue that the use of ‘intended purpose’ in the EU MDR and IVDR, alongside the frequent reference to ‘intended use’ in the legislation, could be considered (from a technical perspective, but not necessarily a legal perspective) to treat intended use and intended purpose as synonyms just like ISO 14971:2019. My personal opinion is that they can be treated synonymously and efforts to make them distinct could lead to more confusion in interpretations and usage.

| ISO IEC Guide 63:2019 | 3.4 intended use use for which a product, process or service is intended according to the specifications, instructions and information provided by the manufacturer (3.6) Note 1 to entry: The intended medical indication, patient population, part of the body or type of tissue interacted with, user profile, use environment, and operating principle are typical elements of the intended use. |

| IMDRF/GRRP WG/N52 FINAL:2024 | 3.14. Intended Use / Intended Purpose: The objective intent regarding the use of a product, process or service as reflected in the specifications, instructions and information provided by the manufacturer. (Modified from GHTF/SG1/N77:2012) NOTE 1: The intended use/intended purpose are also part of promotional or sales materials or statements, although these materials lie outside the scope of this document. NOTE 2: The intended use can include the indications for use. |

| EU MDR 2017/745 | Art 2. (12) ‘intended purpose’ means the use for which a device is intended according to the data supplied by the manufacturer on the label, in the instructions for use or in promotional or sales materials or statements and as specified by the manufacturer in the clinical evaluation; |

| EU IVDR 2017/746 | Art 2. (12) ‘intended purpose’ means the use for which a device is intended according to the data supplied by the manufacturer on the label, in the instructions for use or in promotional or sales materials or statements or as specified by the manufacturer in the performance evaluation; |

| 21 CFR 801.4 | The words intended uses or words of similar import in §§ 801.5, 801.119, 801.122, and 1100.5 of this chapter refer to the objective intent of the persons legally responsible for the labeling of an article (or their representatives). The intent may be shown by such persons’ expressions, the design or composition of the article, or by the circumstances surrounding the distribution of the article. This objective intent may, for example, be shown by labeling claims, advertising matter, or oral or written statements by such persons or their representatives. |

Table 1. Collated definitions of intended use

Regardless of the source, ‘intended use’ can be summarised as “the use of a device, product or service as intended by its manufacturer”. The intent of the manufacturer can be communicated and conveyed via various forms, depending on the source material for the definition.

But what does that mean in practice?

With the definition sorted we can then dig into more detail of what it means in the context of the medical device industry. For this I prefer to fall back on two standards and their associated guidance documents (all about risk management, who’d have thought it?):

- ISO 14971:2019 Medical devices — Application of risk management to medical devices

- ISO/TR 24971:2020 Medical devices — Guidance on the application of ISO 14971

- IEC 62366-1:2015/Amd 1:2020 Medical devices Part 1: Application of usability engineering to medical devices

- IEC/TR 62366-2:2016 Medical devices Part 2: Guidance on the application ofusability engineering to medical devices

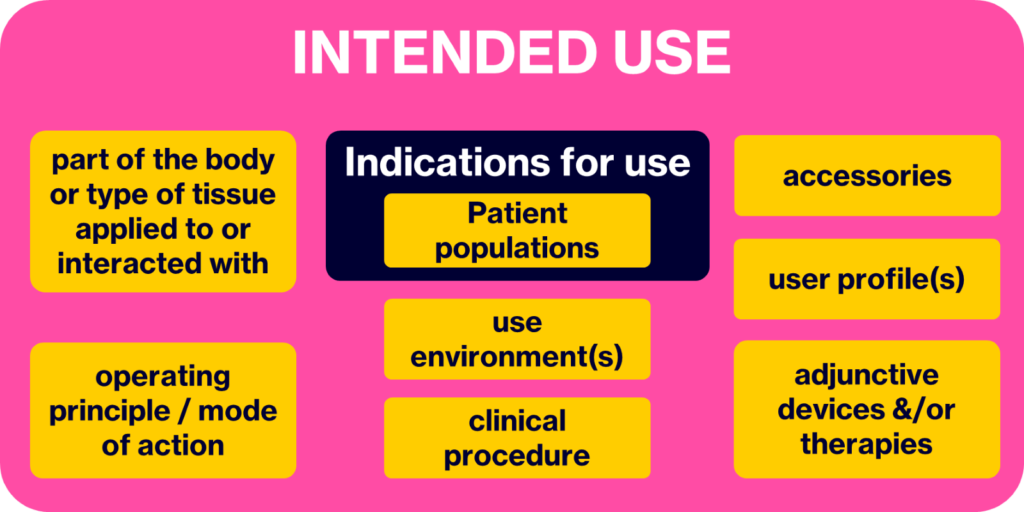

Additionally, the IMDRF definition for intended use indicates that the ‘indications for use’ is a component of the intended use. The IMDRF also add further clarity where IMDRF/GRRP WG/N52 FINAL:2024 also defines ‘indications for use’ and positions the intended patient population as a component of the indications for use. Appreciating the relationships between these terms (see Figure 1) and how they combine to build the overall intended use is key. A thorough understanding of the intended use, and the subsequent development and post-market activities, are fundamental to effective product stewardship.

In summary, it boils down to the answers to key questions along the lines of: Who? What? Where? Why? When? How?

Figure 1. The building blocks of the intended use

Therefore, a reasonable description of what comprises the intended use can thus be summarised as the intended:

- medical indication(s), including patient population(s) and sub-populations,

- part of the body or type of tissue applied to or interacted with,

- user profile(s), e.g.

-

- analytical user vs clinical user (for IVDs, other diagnostics, measuring devices and classification tools),

-

- professional vs lay-person,

-

- role of professionals in the life cycle of the device,

- use environment(s), e.g.

-

- clinical setting vs home setting vs others (e.g. a school, public spaces),

-

- large, state-of-the-art hospitals vs rural community hospitals vs multidisciplinary outpatient clinics,

-

- operating principle / mode of action (of the device),

- clinical procedure (i.e. for the use of the device etc.),

- clinical context (e.g. where/when in the clinical pathway will the device be used?),

- accessories (i.e. used to fulfil the intended use of the device),

- adjunctive devices &/or therapies (i.e. used in conjunction with the device for its intended use, or typically in use on/by the intended patient population).

With this in mind, it should be evident that this holistic view of the intended use (Firgure 1) is then crucial for all the efforts to develop the product (e.g. setting the scene for design and development inputs, framing the context for the risk analysis), traverse the chosen/prescribed conformity assessment pathway (e.g. classification, clinical evidence strategy) and actually market and sell the device to the intended customers and users (e.g. reimbursement, customer sales).

“I hear what you’re saying, but our device is really complicated, and the intended use is tricky to pin down”. I’m not buying that argument! Apply the simplistic logic described above and you will understand, and be able to describe, your intended use much better than before. Regardless of the technology or product type, asking these simple questions helps you understand your product, helps you identify safety characteristics and potential risks, and helps you generate objective evidence to demonstrate that your device is safe, effective and (hopefully) cost-effective for its users.

What happens if insufficient detail is given in the description of the device’s intended use? Therein lies protracted development timelines and delayed market launches. For example, delays can occur due to things like clinical evidence not aligning to the intended claims, or because the clinical data does not address all of the indications for use, or the usability of the user interface has not been assessed for all of the intended user groups.

Insufficient detail in describing the intended use can also lead to troubles in the post-market phase, during post-market surveillance. For example, with the need for multiple design changes required to adjust to multiple customer requirements that were not considered during development, or performing many iterative cycles through the risk management cycle as new use errors and hazardous situations are identified as the difference between the anticipated use and the actual use becomes apparent. More on the last one to come in a subsequent blog.

Is there ever a final intended use?

Only in the same way that there is a design freeze or design lock for the design of the medical device. It is a state of being, but it is not permanent. Change is a constant (someone wiser than me said that I think), otherwise there would be no need for change management activities.

For any organisation thinking that the intended use defined at the start of the design and development inputs or that defined in a regulatory strategy is the definitive intended use, think again. There are numerous anecdotal tales of EU MDR submissions where the intended use has been refined over time but has left a misalignment between the clinical evaluation, and/or the risk management, and other parts of the technical documentation. In reality, we start with a rough outline of the intended use as we start product development. Over time, we add detail to that outline and we edit as we move along, uncovering new evidence, making new decisions. Maintenance activities occur naturally during the life cycle of the device, modifying and updating your device, objective and parameters.

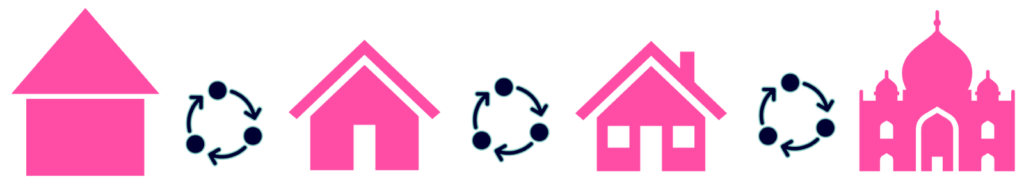

As Figure 2 suggests, the general outline is often in place from the start but by the time we launch the device to market, or many years after initial launch, the outline may have changed with time and/or may have been updated as our understanding of the details increases.

Figure 2. The iterative nature of the intended use throughout the medical device life cycle (travelling left to right)

And all of this leads into the realisation that the identification of reasonably foreseeable misuse, including off-label use is not as difficult as some in the industry make out. If we see the intended use as something that is iterative, that evolves through development and life cycle management (Figure 2), then reasonably foreseeable misuse can be anticipated (often by channelling your inner 3-year-old and just asking, Why? or What if?). When the intended use does change, that change should be managed just like any other change at that stage of the life cycle (e.g. a design and development change, change control of a marketed product). That is not to say that all such uses will be anticipated, in the same way that we cannot be expected to identify every possible risk during product development. The unknown unknowns are there to be uncovered.

As the medtech landscape grows more interconnected, personalized, and fast-moving, good product design should be our driver not simply regulatory compliance. ‘Intended use’ is not merely a checkbox; it’s the architectural blueprint of regulatory success, clinical relevance, and commercial viability. Misunderstand it, and you risk misaligning every downstream function. Join me in Amsterdam at the 2025 International Conference on Medical Device Safety Risk Management, where I will unpack these nuances with clarity, dry sarcasm, and maybe a little regulatory heresy. Let’s stop treating intended use as an afterthought and start treating it as a living hypothesis that evolves with our technologies, our users, and our responsibilities.

Bibliography:

- ISO IEC Guide 63:2019 Guide to the development and inclusion of aspects of safety in International Standards for medical devices

- ISO 14971:2019 Medical devices — Application of risk management to medical devices

- IMDRF/GRRP WG/N47:2024 (Essential Principles of Safety and Performance of Medical Devices and IVD Medical Devices

- IMDRF/GRRP WG/N52 FINAL:2024 (Principles of Labeling for Medical Devices and IVD Medical Devices).

- 21 CFR 801.4 Meaning of intended uses (last checked 11 April 2025)

- ISO/TR 24971:2020 Medical devices — Guidance on the application of ISO 14971

- IEC 62366-1:2015/Amd 1:2020 Medical devices Part 1: Application of usability engineering to medical devices

- IEC/TR 62366-2:2016 Medical devices Part 2: Guidance on the application of usability engineering to medical devices

- EU MDR 2017/745

- EU IVDR 2017/746